Fetishism : Allan M. Hillani

|

Fetishism : Allan M. Hillani Perhaps it would be wiser to let obsolete theories fall into oblivion,

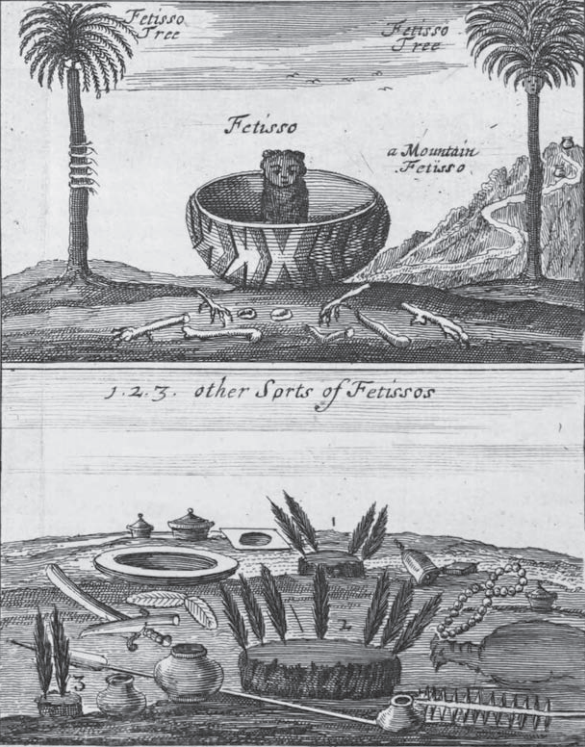

1. Introduction Few concepts in the history of Western thought are more equivocal than fetishism. The term was invented in the eighteenth century by the French writer Charles de Brosses to describe the logic of religious “fetishes,” which conveyed almost any form of direct worship of animals, plants, stones, or artifacts.2 It was intended as a novel contribution to the history of religion, a name to describe the most “primitive” religious practices, fated to develop into polytheism and, finally, monotheism. Given all the problems of such evolutionist theories, it is not surprising that, with the expansion of ethnographic knowledge and a better understanding of so-called fetishistic practices, the concept of fetishism was dismissed by someone like the anthropologist Marcel Mauss as an “immense misunderstanding between two civilizations.”3 While “fetish” as a term could still be preserved in the anthropological discourse to refer to a certain group of so-called “power objects”—the nkisi of the BaKongo, the suman of the Ashanti, the vodu of the Ewe, the butti of the Teke, the ndet of the Yakö, the boliw of the Mande, as well as other worship objects of African peoples—the notion of fetishism, as a conceptual tool, was considered beyond salvation.4 Despite this resistance among anthropologists and historians of religion, the pejorative concept of fetishism proved to be a quite useful misunderstanding, with the notion almost acquiring a “life of its own,” like the objects it attempted to describe. From Marxism to psychoanalysis, from art to popular culture, the term’s meaning and technical usage became so vast that it is almost impossible to speak of “fetishism” in general. What is most interesting in its dazzling conceptual history is how fetishism started to be employed to explain not the “other” of modernity, but the moderns themselves. Following the inversion made first by Marx, and later by Freud, fetishism started to describe not the otherness of the other, but the otherness within oneself, the stranger in the heart of modern practices and ideas. In a similar fashion, my attempt to recast the critical potential of fetishism as a political concept aims to portray an image of the moderns in which they would not typically recognize themselves—one in which we are the fetishists. Fetishism should then not be taken as a problem reserved, perhaps, to the supposed primitive peoples, who submit to “magic objects” and “invisible spirits,” for it has more to say about our enlightened conceptions and practices than about the “beliefs” attributed to others—something often made inaccessible by our narcissistic tendency to mock anything that is not our own reflection. I propose to define fetishism as the stabilization of an ontological equivocation that simultaneously conceals the relational character of the thing it fetishizes. As I will show, fetishism first took the form of the colonial projection that misunderstood the relational context of native practices, but even in Marx and Freud’s analyses the equivocation between self-standing objectivity and relational constitution is central. My contribution is to expand this conceptual structure to analyze how modern political relations are intellectually conceived and unconsciously reproduced by the same kind of fetishization, revealing how the divide between persons and things and the centrality of agency in modern politics, in fact, conceal the constitutive relationality of what these terms designate. This is not simply a misunderstanding, for it produces a distinctly modern political reality, one which we must understand in order to criticize. 2. An Immense Equivocation The seeds for this critical and reflexive turn of the concept of fetishism can be traced back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, where the term “fetish” appeared for the first time in the colonial encounter between Portuguese merchants and the natives of the African west coast—hundreds of years before de Brosses’s attempted systematization.5 What can be perceived in that context is how the truth-dimension of what is called fetishism lies not in its capacity to adequately explain the ritual objects of African natives, but in naming what these objects were turned into in a space of commercial, cultural, and even “spiritual” exchanges, where heterogenous worlds had to find a common tongue. Quite literally, in fact, given that the Portuguese term that originated the word “fetish” (feitiço, “spell” or “charm”) became fetisso, a pidgin term used both by Africans and Europeans to name each other’s sacred objects.6 This applied to the objects of native worship, but also to things like the Bible, commonly used for oaths between Europeans and Africans. In fact, the Bible “fetish” played a very important role, for it allowed European merchants to establish permanent and trustworthy trade relations with the natives, all participating in the “making” of that fetish, thereby guaranteeing the pact’s fulfillment.7 In any case, it must be noted how “fetish” was not a clearly defined object within a specific culture or religious order—neither of the Africans or the Europeans—but something that emerged between them, a form that took shape through their encounter. In what is considered the most authoritative account of fetishism, William Pietz draws out four main characteristics of this strange object: 1) Materiality: The fetish is irreducibly material, a tangible thing; 2) Composition: the fetish is the product of a fixation of heterogeneous elements into a new identity—the “raw materials,” spiritual powers, and the ritual procedure through which the fetish was made; 3) Power: the fetish is an index of how material bodies are affected by material objects thought to have the power to mobilize affects, acts, desires, health, etc.; and 4) Value Relativity: the fetish’s value has a “double character,” given that it is always relative—something that became explicit in the transactions made between puzzled Europeans and natives.8 Of all characteristics, the last one is noticeable for necessarily including the European foreigner, who could no longer ignore the fetish’s reality despite their own disbelief. The fetish’s “value,” after all, did not reside in the evaluation of either the native or the foreigner but only in the product of their interaction and the common space it produced. The result of including the contrast between European and native perspectives is not simply that the “value” of the fetish is taken to be relative, but that its very reality as fetish is shown to be relational: it can only become a fetish through the encounter of their different standpoints. Fetishism, then, is not simply a “misunderstanding,” as Mauss claimed, but what the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro calls an equivocation: it reveals not how different perspectives see the same “thing”—in the end an epistemological problem—but how an internal difference in the “thing” itself is revealed by the encounter of different perspectives.9 The notion of equivocation is based on Viveiros de Castro’s account of Amerindian perspectivism and names the “referential alterity” that different perspectives can have. Perspectivism is here understood as a conception shared by many native peoples of the American continent according to which the world is inhabited by various kinds of “subjects,” human and non-human, each apprehending different realities from a comparable point of view.10 Viveiros de Castro’s description of Amerindian Perspectivism develops from a critique of cultural relativism: it does not propose that different peoples (and different beings) have multiple points of view over the same “objective” world, but that they share the subjective position that is entailed by having a perspective, even though their different bodies and social relations make them see and inhabit different worlds. A corollary that results from this inversion is that the way humans perceive these other subjectivities—animals, gods, spirits, the dead, plants, meteorological phenomena, sometimes even artifacts—is different from the way these beings see humans, even though humans and non-humans see themselves in the “same” way. As Viveiros de Castro explains,

The emphasis on the corporeal attributes and the concrete actions of these beings is crucial for it highlights how “perspective” in the perspectivist framework should not be interpreted as a “mental representation.” Perspective is how the world appears to a subject—be it a “human” person or a non-human one, like a jaguar or a tapir. In fact, to have a perspective is what makes a subject a subject—and the reason why all beings with perspective see themselves like humans see themselves. But this generalization of the subjective position does not produce the same effect in the objective world. Different perspectives do not see the same world differently; they are inhabiting different worlds altogether—the world of the jaguar differs from that of the humans, which differs from that of the tapir, which differs from that of spirits, and so on. Reality is “objective” for each perspective, but the objective reality changes from one perspective to another. From the perspective of the jaguar, what we see as blood is beer; but no one (neither us or the jaguar) sees “blood-beer”; we see either blood or beer. For Amerindian perspectivism, then, one’s world is recognized as ontologically relative, thereby making any object potentially equivocal—i.e., different depending on the perspective seeing it, despite the fact that, for every perspective, its “reality” seems unquestionable. The perspectivist problem of equivocation is then not that of discovering the common referent of two different “representations”—in the case of fetishism, what the Portuguese explorer and the African native understood both by fetisso, for instance. The problem is rather how the equivocation between two different perspectives can make it seem as if both are talking about the same thing, when they are in fact seeing in the same way (“objectively”) different things.12 What the “fetish” is depends on the relations, conceptions, ways of being in the world that characterize each perspective. But what must be noted is that the Western concept of fetishism ends up concealing this equivocal structure by taking its own position as the only “objective” and real one, completely independent from the other’s perspective (which is described as a “belief” in things like sorcery, spirits, and powerful objects). By taking for granted that the Western perspective sees how things “really are,” it ignores how it is, in the end, still a perspective. The other is guilty of “believing” in fetishes just because the Western perspective takes its own distinction between belief and reality to be ultimately real. It poses its own premises as the only ones corresponding to reality and dismisses all others as mistaken, ignoring that the practical relativity of the fetish—that it can only exist between perspectives—exemplifies how reality can itself be relational. When we analyze the equivocal condition of fetishism, we can notice that, in fact, “fetish” only names the common referent of two perspectives insofar as it encompasses the other one as mistaken. An object is only a fetish because the other is taken to be a fetishist who believes in its power, magic, divinity, when nothing of the sort is “actually real.” There is a double assumption in place, each grounding the other: first, that such object is powerful for the other and not for oneself; second, that this attribution of powers is mistaken, since the object is clearly “just an object.” This is why fetishism emerged from the colonial encounter of perspectives: it depends not only on the perspective that sees an ordinary object as enchanted, but precisely on the encounter of this perspective and the perspective that calls the former “fetishistic”—the latter encompassing the former as mistaken. Fetishism is thus always the fetishism of the other. The concept of fetishism must then be understood as a colonial projection of Western thought upon its other, one that turns an ontological equivocation into a supposed epistemological error. In this sense, an analysis of fetishism reveals more about the assumptions of Western thought than about the supposed fetishists themselves. For instance, one of the crucial aspects of de Brosses’s elaboration of the concept—and what allowed him to generalize vastly different practices across Africa, the Americas, Asia, and even the Greek and Roman worlds as forms of “fetishism”—is that the object of worship in fetishism is the fetish itself, not a divinity beyond it. The fetishist is taken to think that the fetish, a material object that has nothing special about it and is often made by its own worshippers, is itself a divine being—instead of a representation of one, as in the case of idols, for instance. The idea that gods can be “made real” (and not just “made up”) is unacceptable for Western thought; it doesn’t fit the notion of “divinity” as something that is beyond human influence. Fetishes are material objects; gods are immaterial; therefore fetishes cannot be gods.13 However, what the natives accused of fetishism see in material objects is the embodiment of myriad relations between them, their environment, other peoples, as well as animals, plants, gods, spirits, the dead, etc., all of them coexisting in the same cosmopolitical plane. A Maori gift, for instance, might have a “spirit” because it is a detachment from the person of the giver; a Congolese nkisi might be effective only if the right materials are assembled in the right ways, given how different materials (including material bodies) interact in different ways; gods like the orishas of Yoruba religion might exist only insofar as the community that makes them continues to exist, and so on.14 Gods, things, and people can be “made” because making is just an enactment of their relationality—it is the removal of gods from the material realm, and things from the spiritual realm, that ends up “fetishizing” both of them. In fact, I might add that this fetishization of materiality is a problem even from a scientific perspective. One of the outcomes of quantum theory, for instance, is precisely that objectivity cannot be thought outside of the interaction between observer and phenomenon, making the idea that matter is something inert and objective simply untenable.15 While the standard modern perspective on fetishism assumes that the native is a fetishist who is incapable of “representation” and mistakes ordinary things for animate beings, from the native’s point of view, it is the Westerners who fail to see how things really embody relations that are constitutive of what they are, and without which they simply would not exist. This is because relations are not something that exist between already constituted entities; they are constitutive of these entities themselves. This inversion is found not only in the colonial encounter between Africans and Europeans in the early modern period, but in several other encounters between so-called “fetishists” and “animists” and their future colonizers, be it in Africa, Asia, Oceania, or the Americas. The generalization of the “other” of Western modernity is ticklish, for it risks producing a negative generalization that is itself colonial in nature (everything that is not Europe must be the “same”).16 But the effort of understanding this “other” of modernity as precisely an other—an otherness found even within Western modern thought itself, as I will claim is the case with the critical theory of fetishism—is still pertinent. If I am then allowed to generalize: for the modern subject, the native mistakenly thinks that the fetish-object is “autonomous” like a person, but what the native perspective reveals is that both persons and things are what they are because of the relations in which they are enmeshed, and not despite them—neither persons or things are “independent” or “self-standing” in this sense. The ontological relativity of the fetish reveals how relations do not exist “between” entities—external to discrete and self-contained terms—but “within” them.17 It reveals how even the power of a “divine object” is based on the relations it is able to embody, not a kind of supernatural distortion of physical capacities. Only an individualistic tendency to turn the systematicity of differences into a collection of essentialized entities could assign the appearance of ontological self-sufficiency to both persons and things—a trait that is so typical of the “civilized” thought of the moderns.18 Fetishism, as I propose to understand the term, is the spontaneous philosophy of modernity; not a trait of its opposite, nor a primitive remnant, but the fundamental aspect of how the moderns relate to the world. 3. Objectivation and Disavowal So far fetishism has been described as the attribution of independent capacities that, nevertheless, are shown to depend on relational contexts. This definition exposes that it was, in fact, the moderns who “fetishized” the so-called fetishes of the natives. But what is equally crucial is that this fetishization is successful only because it is not recognized as such; it must be somehow erased, or at least ambiguously registered. By unveiling such process of concealing, the concept of fetishism acquires a critical dimension—one that is able to reveal the relational constitution of so-called fetishes. This shift was central to the contributions of both Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, who subverted fetishism into a critical concept employed against the standard view in modernity. As I argue in what follows, both Marx and Freud propose the simultaneous denunciation of the fetish-object’s removal from its constitutive relations and an explanation of how this removal can nonetheless be “real,” that is, produce effects of its own. What Marx calls the “fetish-character” of commodities in Capital aims to explain how the “obvious, trivial thing” we call a commodity is, in fact, a “very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”19 At stake is how the relationality of value can be objectified as an intrinsic property of commodities, and how this objectivation of relations allows things to control us, rather than the other way around. Fetishism, for Marx, thus names a double process involving the “personification” of objects and the naturalization of social attributes. More precisely, it is through the naturalization of social attributes that objects can appear as persons imbued with opinion, desire, caprice, etc. Marx attributes the personification of commodities to the “mysterious character of the commodity-form,” which enables the products of labor to acquire “objective characteristics” and “socio-natural properties,” namely a value that is distinct from the commodity’s material shape.20 This process allows social relations among producers (the social division of labor, the process of exchange, etc.) to take on the form of a material relation between producers and products and a social relation between things. It is because a social relation is “naturalized” (i.e., it appears as a natural property) that the object of the relation can be personified (i.e., it appears to possess human-like attributes).21 This process is not simply a misperception. Commodities really embody a whole economic system in their objective values—the value of a single commodity already designates a whole network of comparative values among other commodities—but they do so only through the context of the exchange relations of which their value is part. From the standpoint of the exchanger, commodities really have value—in the market, one cannot “demystify” anything; one can only decide whether to exchange or not. Yet, commodities reallyhave value only because of the network of relations of the entire world of commodities. One can only denounce the mystification of this process by shifting from the perspective of the exchanger to the speculative perspective of commodities themselves, where the relations they establish with each other become central. The “removal” of the commodity from its relational context only appears through the shift from the commodity’s standpoint to that of the exchanger.22 Commodity fetishism emerges as a practical solution to the equivocation between the standpoint of the exchanger and the standpoint of the commodity. At the level where commodities relate to one another (and where they appear to each other), there is no fetishism in the strict sense (commodity A, say, is exchanged with commodity B, thereby validating an equivalence of value). But this realm of commodities appears to the exchangers as being made possible because of some “supersensible” property intrinsic to commodities themselves, thereby erasing the network of relations of commodity exchange and objectifying what are fundamentally relational properties (commodity A has a value X, independently of commodity B). This is what characterizes fetishism “in itself,” so to speak, because the exchangers do not acknowledge any objectification. The perspective that enables one to understand fetishism as fetishism (not only “in itself” but “for itself,” to keep up with the Hegelian language) emerges from an awareness of the perspectival equivocation between the two standpoints. It is this third perspective (not the perspective of the commodity, nor the perspective of the exchangers) that can give way to a “critique” of fetishism—and, not by chance, is the perspective assumed by Marx himself. But notice that this critical stance is not removed from the equivocation as a more “objective” description of what is going on between commodities and their exchangers. It is not a purely external standpoint—like the neutral scientific standpoint sought by de Brosses, for instance—but the result of speculatively posing the perspective of the commodities, which reveals how objectified relations appear to the exchangers as a natural fact. Like the drawing of a cube on a blackboard, where three dimensions emerge out of two, the critical standpoint only exists as an effect of the interplay between the other two perspectives. This means that fetishism cannot be reduced to a matter of “false consciousness,” although its unconscious aspect is indeed crucial. Surely, contractual and exchange relations are consciously enacted. We know very well what we are doing when we buy a commodity, but the point is that the social relation of equivalence produced by this purchase is not the result of a conscious decision. It is not because they recognize the equivalence between the value of two commodities (and, correspondingly, the equivalence of the labor necessary to produce them) that people exchange them, but the other way around: it is because people exchange commodities that they equate their labor and validate the value of their products. “They do this without being aware of it,” as Marx puts it.23 But even if they knew, fetishism is socially imposed in a way that is independent from their individual opinions and beliefs. As Alfred Sohn-Rethel famously argues, value is a real abstraction precisely because it is independent of the mental abstractions of the individuals involved.24 This unconscious dimension of fetishism recognized by Marx takes center stage in the psychoanalytic interpretation of the phenomenon, despite Marx and Freud’s concerns and approaches being quite distinct. Fetishism, for Freud, is a specific kind of perversion that operates through a substitutive sexual object (along with the disavowal of that very substitution). “The fetish,” explains Freud, “is a substitute for the woman’s (mother’s) penis that the little boy once believed in and—for reasons familiar to us—does not want to give up.”25 The “familiar reasons” alluded to here refer to the castration complex: the unconscious fear that, if the mother (and, by extension, women in general) does not have a penis, it must be because she was “castrated”—and the same might happen to the boy. The fetishist is someone who neither overcame the belief that women are supposed to have penises, nor preserved that belief untouched; instead, says Freud, he paradoxically “retained that belief, but he has also given it up.”26 This contradictory solution, for Freud, produces a “splitting of the ego” where two contradictory premises coexist side by side due to the compromise formation resulting from the substitute object—namely, the fetish, which stands for the supposedly absent sexual organ.27 Fetishism is then only possible due to both an acknowledgement and a repudiation of reality characterizing what Freud calls disavowal (Verleugnung).28 For Freud, disavowal is an unconscious defensive mechanism that attempts to erase the registration of a disturbing reality, but that, in doing so, allows it to be registered otherwise. On the one hand, the fetishist registers the absence of the phallic organ in the female body as a problem, triggering the defensive mechanism; yet, as Freud puts it, he is also unconsciously “recognizing the fact that females have no penis and are drawing the correct conclusions from it.”29 The ego is split in two by simultaneously registering both claims—that females should have a penis and that they should not—which ends up splitting reality itself for the fetishist. It is important to note that fetishism does not stage a conflict between fantasy and reality, but rather reveals a certain conflict between two realities—the “external” reality of sexual difference and the “internal” or psychic reality of the castration complex—and two fantasies: one in which females are not castrated and another in which castration is indeed a real threat. On the one hand, fetishism is anchored in the reduction of sexual difference to a phallic monism according to which there is only one sex (the male one), either present or absent. The fantasy of the fetish replacing the absent penis is based on another fantasy, one that precisely frames sexual difference as absence.30 On the other hand, fetishism is a real defense mechanism triggered by the psychic reality of the threat of castration, which in turn results from the registration of the “external” reality of sexual difference. Sexual fetishism would then entail a double disavowal: the registration and repudiation of sexual difference produces a fantasy of phallic monism, but then the absent phallus is also simultaneously registered and repudiated, finding its solution in the adoption of the fetish. In a certain way, the fetish is a “solution” to a problem the fetishist himself (unconsciously) created. That fetishism emerges out of the disavowal of sexual difference allows it to be generalized beyond a specific kind of sexual perversion. Disavowal is not exclusive of sexual fetishism, but a psychic mechanism that produces a compromise formation between the psyche and “external reality,” just like repression (Verdrängung) protects the psyche from its “internal” demands.31 This explains why Freud will link fetishism to potentially all forms of love in the Three Essays, claiming that loved ones are always “overvalued,” their attraction not being reducible to their sexual organs.32 It also justifies Freud’s comparison between castration anxiety and the “panic when the cry goes up that Throne and Altar are in danger,” another instance where a fetishist solution creates the very problem it proposes to solve.33 Fetishistic disavowal allows the erotic drive to be both displaced and kept in place, reality to be registered and repudiated, connections to be unconsciously acknowledged and consciously denied, thereby allowing certain things and persons to stand for a complex set of unconscious relations that are never recognized as such. Similar to Marx’s standpoint regarding commodity fetishism, Freud’s standpoint can only emerge by speculatively posing the standpoint of the unconscious in relation to how people consciously perceive the world. Fetishism emerges from the equivocation between external and internal reality, conscious perception and unconscious fantasy—an equivocation that is stabilized by the sexual fetish and can only be brought to consciousness through the process of analysis.34 Fetishism for both Marx and Freud stabilizes an equivocation between two perspectives whose conflict reveals the relational character of objective reality. The fetish-object can only be an objectivation of relations because one perspective disavows the other: on the one hand, the fetish is relationally constituted, on the other, it really takes the form of an independent object. That this can be called “fetishism” results from recognizing the equivocation between the two dimensions—that is, acknowledging both its relational character and the reality of its objectivation. As a result, commodities are perceived as having value independently from all other commodities and being capable of dominating their owners, just like sexual fetishes are perceived as themselves erotic, independently of the missing part they substitute for. 3. Person and Things, or the Fetishism of Agency The concept of fetishism then names the process through which a perspectival equivocation is stabilized by means of an unconscious objectivation of relations. This objectivation produces a specific form of social reality where relations are concealed and entities can appear independent and unrelated. But I am not just interested in understanding fetishism in general. What I think is puzzling and has not yet been properly analyzed is the fetishism of political relations, namely, how political relations can be similar to the other instances of fetishism as analyzed by Marx and Freud. The way in which political relations are fetishistic is not straightforward. It seems reasonable to suppose that, given that fetishes are typically understood as “objects,” a natural path for analyzing political fetishism would be to examine situations in which objects have a political relevance—crowns, thrones, scepters, government buildings, royal portraits, official insignias, monuments, etc. The problem with this approach is that it overlooks the fact that fetishism is not just about the “power” of objects, but rather reveals something about the logic of power itself—namely how powerful things are, in fact, very similar to powerful persons. Actually, the way fetishists are taken to improperly ascribe power to things works in exactly the same way as we ascribe power to persons—when it comes to power, the difference between persons and things does not really make a difference. This is not to claim that there is no distinction between persons and things, but rather to suggest that what counts as a “person” or a “thing” can itself be relative—a relativity concealed by what I am calling political fetishism. The history of fetishism’s equivocation offers an excellent example of how things that some regard as mere objects can be taken as persons by others. Conversely, labor relations and sexual desire are classic cases in which persons from a certain standpoint can instead be taken as things. But if, from its origins, the notion of fetishism has been concerned with the inappropriate “personification of things,” the true question of political fetishism is how persons themselves become “personified”—and how personhood and thinghood came to be ontologically distinct in the first place. The problem of the personification of persons is relevant because politics always takes place between persons. Sure, political relations depend on a material infrastructure that is not neutral and influences these very relations35 and, as Bruno Latour notes, what differentiates typically human political formations from the politics that takes place among apes, for instance, is not the direct “interaction” between persons, but, most importantly, the ability to turn social relations into thing-like structures that persist even after the interaction is over.36 But this means that “politics” in general takes places only through the interaction of persons, even when they are mediated by objects, and even when those persons are not human. In other words: For things, animals, and other nonhuman beings to be included in the realm of politics, they must be recognized as persons on some level. The fact that politics is the business of people—but that the very definition of what constitutes a person is itself a matter of political dispute—has prompted authors such as Latour to call for an expansion of the beings included within our political deliberations so as to form a “parliament of things,” as he calls it.37 In this expanded parliament, political representation would be more plurally distributed, including entities like the ozone layer or the chemical industry. However, merely granting “representation” to things within our political parliaments has the involuntary consequence of leaving unchallenged both our understanding of political relations and the corresponding ontological divide between persons and things. My point is precisely that, instead of just including “things,” we should fundamentally change not only how we conceive them, but also (and more importantly) how we conceive “personhood” itself. The principal criterion separating persons and things appears to be the notion of agency: persons are agents, things are not. Even when people are treated like things they still retain their agency; conversely, when things are treated like people they do not begin to act autonomously. However, isn’t the very conception of “agency,” a property that is inherent to persons and not things, just another case of fetishism? Aren’t we facing an objectivation of relations that can only take place by disavowing its relational constitution—in this case, the relational constitution of the “person” itself, whose agency only exists in a context of relations which includes not only other persons but also things? Perhaps we should abandon the classificatory obsession with separating a group of entities that we validate as persons from another that we invalidate as things and move toward an understanding of how persons and things might assume different roles as agents and patients, depending on the context. The result is not a complete undifferentiation between persons and things, but the understanding that “thinghood” and “personhood” are objectivations of the relations of which they are part, and not an intrinsic attribute of the related terms. By not being a priori concerned with the classification of beings as agents or non-agents, we might achieve a more accurate understanding of how agency itself works—and, consequently, of how political relations operate. We encounter agents in the world not because we are able to identify an agentic attribute in them: we assume that they are agents because of the effects they are capable of producing—because we are patients in relation to their actions. This applies to other people, but also to objects, which are often capable of affecting us in different manners. Agency is just a framework for thinking about social effects, after all. The difference between ascribing agency to potentially everything—as so-called “animists” and “fetishists” do—or restricting it to humans is just a matter of degree. In fact, one of the most interesting points of contact between anthropological theories centered on Indigenous ontologies and the so-called “new materialist” theorists that explore the social implications of scientific discoveries is that both arrive at a very similar understanding of agency: relational, context-dependent, and grounded in networks of interactions between agents and patients that are not restricted to human beings.38 Recognizing the relationality of agency is a crucial step in developing a theory of political fetishism because it allows us to understand political fetishism as different forms of severing agency from its relational context—either by congealing agency into a capacity, like in the case of power, or by personifying collective forms because of their capacity to act upon us, as with State institutions. This means that the problem of including “things” in politics arises only if we stick to a fetishistic understanding of agency. If it is true that politics always takes place between persons what matters is that what counts as a person (and what is reduced to a thing) is itself under political dispute. For this reason, the philosopher Isabelle Stengers proposes that we rethink politics as a fundamentally diplomatic practice—a conception quite different from the deliberative model we have inherited from the Greeks (and which Latour has extended to non-humans with his idea of a “parliament of things”).39 To conceive of politics as a diplomatic practice is to recognize that the status of political actors is also under dispute, meaning that it emerges only through the very process of interaction and by the sheer fact that actors must interact somehow. This diplomatic shift reveals the fundamentally speculative dimension of politics, a feature it shares with diplomatic activity itself. Diplomats are not required for negotiations with those already familiar to us, but precisely for mediating the interaction with entities that are completely different from (and potentially hostile to) us. They intervene where war seems a logical outcome and strive for peaceful articulation of commitments, without any guarantee that they will succeed. There is no privileged standpoint in diplomatic negotiations—one can only speculate about the position of the other. It is this speculative dimension of politics that characterizes its fundamental unpredictability—a feature that, within the deliberative model, can only exist within a stable and well-defined arena. By not having assumptions about the entities entangled in diplomatic relations, the diplomatic model allows us to conceptualize an ontological politics in which neither the arena nor the disputing parties are determined a priori. To conclude, we might learn from the history of fetishism and realize that our projections regarding the supposed power of things might have more to say about our current political institutions and conceptions than it is usually taken to be the case. When we try to think in non-fetishistic terms, we find relations all the way down, relations which are constantly being sliced into fetishistic persons and fetishistic things ignoring the ontological politics involved in the production of both of these entities. To propose a theory of political fetishism is a way to highlight their relational character, as well as to explain their effectiveness beyond simple misbelief. Properly understanding the fetishistic character of modern thought about politics, power, and the State is a first step in order to provide a critique worthy of its name. Published on July 19, 2025 * Allan M. Hillani * 1. Claude Lévi-Strauss, Totemism, trans. Rodney Needham (Boston: Beacon Press, 1962), p. 15; trans. mod.↩ 2. Charles de Brosses, “On the Worship of Fetish Gods: Or, a Parallel of the Ancient Religion of Egypt with the Present Religion of Nigritia (1760),” in Rosalind C. Morris and Daniel H. Leonard, eds., The Returns of Fetishism: Charles de Brosses and the Afterlives of an Idea (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).↩ 3. Marcel Mauss, review of At the Back of the Black Man’s Mind: Or Notes on the Kingly Office in West Africa by R.E. Dennett, L’Anée sociologique 10 (1905): 309.↩ 4. An example of a defense of the notion of fetish against that of fetishism is Jean Pouillon’s Fétiches sans fétichisme (Paris: François Maspero, 1975). Here, I will argue almost the opposite: a critical defense of the notion of fetishism reveals the inherent equivocation of the notion of fetish.↩ 5. See William Pietz, The Problem of the Fetish, ed. Francesco Pellizzi, Stefanos Geroulanos, and Ben Kafka (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022); Alfonso Iacono, Fetishism: The History of a Concept (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016); Michèle Tobia-Chaidesson, Le fétiche africain: Chronique d’un “malentendu” (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000).↩ 6. The word “fetish” originates from the Portuguese word “feitiço” (spell, charm), while feitiço comes from the Latin facticius (artificial, made, but also forged, counterfeit). All European languages ended up translating fetisso in one way or another (fetish, fetiche, fétiche, Fetisch, etc.), including Portuguese, which has the specific word “fetiche” to designate fetishes.↩ 7. On the topic, see William Pietz, The Problem of the Feitsh, 58; William Tobia-Chaidesson, Le fétiche africain, 121; David Graeber, “Fetishism as Social Creativity: or, Fetishes are Gods in the Process of Construction,” Anthropological Theory 5:4 (2005): 414. Also noteworthy is how the term was used to name anything the Africans did not want to explain to strangers. Calling them a “fetish” was a quick way to avoid questions and added to the mystery surrounding such objects.↩ 8. William Pietz, The Problem of the Fetish, 5–10.↩ 9. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation,” in The Relative Native: Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds (Chicago: Hau, 2015), 58.↩ 10. See Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2014); and The Relative Native.↩ 11. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, 197.↩ 12. With Donna Haraway, we can claim that this is the only true account of objectivity possible, given that “objectivity turns out to be about particular and specific embodiment, and definitely not about the false vision promising transcendence of all limits and responsibility” (Donna J. Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature [New York: Routledge], 190).↩ 13. See David Graeber, “Fetishism as Social Creativity”; Bruno Latour, On the Modern Cult of the Factish Gods (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).↩ 14. On these examples, see Marcel Mauss, “Essay on the Gift: The Form and Sense of Exchange in Archaic Societies,” in The Gift, trans. Jane I. Guyer (Chicago: Hau, 2016); Wyatt MacGaffey, “Fetishism Revisited: Kongo ‘Nkisi’ in Sociological Perspective,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 47:2 (1977): 172–84; Márcio Goldman, “Histórias, devires e fetiches das religiões afro-brasileiras: ensaio de simetrização antropológica,” Análise social 44:190 (2009): 105–37; and J. Lorand Matory, The Fetish Revisited: Marx, Freud, and the Gods Black People Make (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).↩ 15. See Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Half-Way: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).↩ 16. Conscious generalizations and systematizations that avoid this trap can be found not only in the works of Viveiros de Castro already cited, but also in Claude Lévi-Strauss, Wild Thought, trans. Jeffrey Mehlman and John Leavitt (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021); Phillipe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, trans. Janet Lloyd (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); and Marshall Sahlins, The New Science of the Enchanted Universe: An Anthropology of Most of Humanity, ed. with the assist. of Frederick B. Henry Jr. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022). ↩ 17. See Marilyn Strathern, Relations: An Anthropological Account (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).↩ 18. Just as Western intellectuals managed to reduce the complexity of diverse social phenomena under the guise of “fetishism”—a procedure that has the advantage of allowing comparisons unlikely to occur to those intimately embedded in such things and practices—I propose, rather provocatively, that we similarly gather the conceptions, whether spontaneous or expertly crafted, concerning the intrinsic discreteness of things in the world (a notion that moderns tend to take for granted) and attribute to it a comparable generality. This, I believe, is what is at stake in Bruno Latour’s use of the term “the moderns,” which echoes the way moderns speak of non-modern peoples (the Achuar, the Nuer, the Mexica, de Daribi, etc.).↩ 19. Karl Marx, Capital: Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1: The Process of Production (London: Penguin & New Left Review, 1976), 163. My reading of Capital and the problem of the fetish-character of commodities follows the so-called “value-form theory,” synthesized by Michael Heinrich in An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2004) and How To Read Marx’s Capital: Commentary and Explanations on the Beginning Chapters (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2021).↩ 20. Karl Marx, Capital, 164–5.↩ 21. Karl Marx, Capital, 166.↩ 22. This is why fetishistic relations—such as the one constituting commodity exchange—are not simply “inter-subjective.” Nicole Pepperell demonstrates the pertinence of this distinction in the different analogies mobilized by Marx in the section on the commodity fetish. First, she argues, Marx presents an optical analogy to describe a physical relation between an object and the eye: “the impression made by a thing on the optic nerve is perceived not as a subjective excitation of that nerve but as the objective form of a thing outside the eye” (Marx, Capital, 165). Then Marx presents a second analogy, concerning the “misty realm of religion,” in which the “products of the human brain appear as autonomous figures endowed with a life of their own” (Marx, Capital, 165). However, in Pepperell’s reading, this presupposes a subjective standpoint: the social aspect takes place “in the human brain”; it is inter-subjective, but not properly objective. It is only after presenting these two possible kinds of relations—objective and physical and inter-subjective and social—that Marx introduces his idea of fetishism as both objective and social. The analysis of commodity fetishism is thus “a critique of a non inter-subjective, but social, environment that strikes the social actors who create it as an autonomous material world” (Nicole Pepperell, “The Exorcism of Exorcism: The Enchantment of Materiality in Derrida and Marx,” Ctrl-Z: New Media in Philosophy 2:1 [2012], http://www.ctrl-z.net.au/articles/issue-2/pepperell-the-exorcism-of-exorcism/).↩ 23. Karl Marx, Capital, 166–7; see also Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 1–55.↩ 24. See Alfred Sohn-Rethel, Intellectual and Manual Labour: A Critique of Epistemology (Leiden: Brill, 2021).↩ 25. Sigmund Freud, “Fetishism (1927),” in The Future of an Illusion, Civilization and its Discontents and Other Works (1927–1931), vol. 21 of The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1961), 152–3.↩ 26. Sigmund Freud, “Fetishism,” 154.↩ 27. Sigmund Freud, “An Outline of Psychoanalysis (1940)” and “The Splitting of the Ego in the Process of Defense (1940),” in Moses and Monotheism, An Outline of Psycho-Analysis and Other Works (1937–1939), vol. 23 of The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1964). For an account of the dynamic of belief in Freud’s notion of fetishism, see Octave Mannoni, “Je sais bien, mais quand même… ,” in Clefs pour l’imaginaire, ou L’Autre scene (Paris: Seuil, 1969); Vladimir Safatle, Fetichismo: colonizar o outro (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2010); and Robert Pfaller, On the Pleasure Principle in Culture: Illusions Without Owners (London: Verso, 2014), esp. ch. 2.↩ 28. In Octave Mannoni’s felicitous phrasing, fetishistic disavowal always takes the form of “I know very well but…” with the adverse conjunction being a way of including the “misrecognition” of what one “knows” (see Octave Mannoni, “Je sais bien, mais quand même…”).↩ 29. Sigmund Freud, “An Outline of Psychoanalysis,” 203.↩ 30. See Alan Bass, Difference and Disavowal: The Trauma of Eros (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000), 27–31; Vladimir Safatle, Fetichismo, 63–6.↩ 31. Sigmund Freud, “An Outline of Psychoanalysis,” 204.↩ 32. Sigmund Freud, “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905),” in A Case of Hysteria, Three Essays on Sexuality and Other Works (1901–1905), vol. 7 of The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1953), 154.↩ 33. Sigmund Freud, “Fetishism,” 153.↩ 34. This structure is also found in Viveiros de Castro’s self-implication in his analysis of Amerindian perspectivism. By taking seriously Indigenous people’s attribution of perspective to non-humans, his approach calls into question the very status of the anthropologist’s perspective describing the perspectival encounter between, say, a native and a jaguar. The perspective of the anthropologist is not removed from this perspectival relation because it recognizes itself as a perspective, one that is different from the native’s perspective. However, the anthropologist’s perspective also adds to the picture by showing that perspectivism is not simply a cultural specificity of determinate peoples but a structure that expands beyond it, allowing the anthropologist to recognize their own perspective as a perspective (and, consequently, to put their own position into question).↩ 35. See Langdon Winner, “Do Artifacts Have Politics?,” Dedalus 109:1 (1980): 121–36; John Law, “Power, Discretion, Strategy,” in A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power, Technology and Domination, ed. John Law (London: Routledge, 1991); Bruno Latour, “On Interobjectivity,” Mind, Culture, and Activity 3:4 (1996): 228–45.↩ 36. Bruno Latour, “On Interobjectivity,” 66–70.↩ 37. See Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 142–5.↩ 38. It is important to note that what is at stake is not simply the usefulness of attributing agency to things—i.e., that it is safer “to presume that a boulder is a bear (and be wrong) than to presume that a bear is a boulder (and be wrong).” The attribution of animacy, intention, or agency to non-human beings is not a matter of cognitive error, but of recognizing that in the relations established between persons and things, it does not matter “what a thing (or a person) ‘is’ in itself; what matters is where it stands in a network of social relations” (Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998], 121–3).↩ 39. Isabelle Stengers, “The Challenge of Ontological Politics,” in Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser, eds., A World of Many Worlds (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 83–7.↩ |