Spontaneity : Maya Kronfeld

|

Spontaneity: Maya Kronfeld

4. Toni Morrison’s Drums, the East St. Louis Massacre, and the Silent Protest Parade

1. Introduction

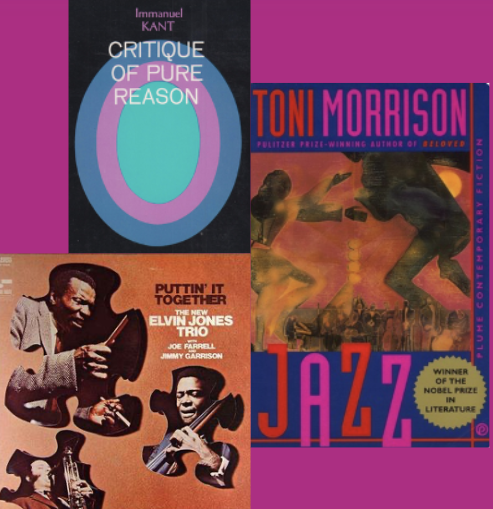

This essay is part of my project of reclaiming the concept of spontaneity for philosophy, jazz, and literature.1 I bring together Immanuel Kant’s notion of spontaneity from the Critique of Pure Reason with Elvin Jones’ album Puttin’ it Together and Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz to address critical impasses around the concept of spontaneity and its cognate term, “improvisation.”2 The racist denigration of spontaneity in jazz, I claim, belongs to the same ideological paradigm that has distorted the popular understanding of spontaneity in its philosophical and literary formations. As much as the improvisational aspect of jazz has been celebrated, discussions of its famous spontaneity have been curtailed and defanged by a reductive reception. Indeed, the term “improvisation,” like the very term “jazz” itself, continues to mark an erasure.3 But Black musical aesthetics have continually defended philosophical possibilities that have been otherwise rendered invisible. The meaning I wish to restore to the concept of spontaneity can be expressed in the phrase “structure in the moment,” which I have proposed elsewhere, from the standpoint of musicians and rhythm section members.4 I need to make it absolutely clear at the outset that the spontaneity that concerns me is epistemic spontaneity; it has more to do with the imaginative underpinnings of knowledge production than with vitalism. This may be confusing to readers steeped in the colloquial use of the term (see section 3 below). My claim here is that verbal and rhythmic art can make palpable the spontaneous possibilities of knowledge-making that are always there but are either negated through structural violence or just ignored. But the epistemic sense of “spontaneity” is exactly what has become muted in the dominant reception of the term.

However, in the Critical Theory tradition, coming out of Kant but not always indexed to him, spontaneity has come to mean nothing less than the possibility of critical thought and change.5 It is, to quote Homi K. Bhabha, who follows Salman Rushdie, “how newness enters the world.”6 Yet Kant’s core idea in the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/87)7 that spontaneity is a constitutive feature of the human understanding—a feature of discursive thought—remains largely indigestible in a culture dominated by empiricist conceptions of the mind, expressed most recently by the Chat GPT craze.8 Counterintuitively perhaps for us today, Kant associated spontaneity not with unstructured flow but with the universal capacity to cognize—to creatively make something of what is perceptually given. Indeed, Robert Pippin refers to spontaneity as that “enigmatic synonym for thinking” in Kant’s philosophical system.9 At the same time, Kant’s notion of the mind’s spontaneity sits uncomfortably with the developmental, primitivist binaries that his own race theory helped consolidate.10 Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz can be positioned as a key intervention in the afterlife of cognitive spontaneity, offering a literary rejoinder to critical quandaries in both jazz criticism and the philosophy of mind that have obfuscated spontaneity’s importance for epistemology. In Morrison, spontaneity re-emerges as a knowledge problem.11 Her novel offers an account where rhythm—in particular the drums, the instrument most criminalized and co-opted by primitivist fantasies—becomes the prototype for an act of spontaneous cognitive judgment in a country where, as James Baldwin put it, “words are mostly used to cover the sleeper, not to wake him up.”12 I join Michael Sawyer here in turning to Morrison’s oeuvre as crucial for an ongoing effort to reclaim the very category of cognition from its imperial trappings.13 Black cultural forms are an essential point of reference from which to theorize neglected dimensions of cognitive spontaneity in Kant’s theory of mind, at the same time that doing so points up the racist entanglements of Kant’s own system, as Charles Mills and others have argued within (and beyond) the rubric of Black Radical Kantianism.14

2. Putting It Together

So again I see my-

“One of the most malevolent characteristics of racist thought,” Toni Morrison writes in her Foreword to the novel Paradise, is “that it never produces new knowledge . . . It seems able to merely reformulate and refigure itself in multiple but static assertions.”16 Jazz music’s emphasis on the new emerges in the epistemological context of white supremacy that Morrison elaborates. In contradistinction to self-replicating discourses, the spontaneity of jazz, like that of the experimental verbal art Morrison herself is crafting, lies in the fervor with which its practitioners have pursued and produced new knowledge. Elsewhere, I elaborate an account of verbal and rhythmic art as spaces for new, not-yet-available concepts, for thoughts not yet thinkable.17

Very often that new knowledge includes encoding an awareness of what has been erased.18 This awareness is what Nathaniel Mackey, drawing on Bessie Smith, describes as the lyrical song-Bird’s “bass note” . . . a “note of alarm at the exclusions by which coherencies tend to be supported.”19 Mackey’s critical work here has an affinity with the philosophical work of Adrian Piper, who deploys the “Kantian Rationalism Thesis” to explicate “the phenomenon of xenophobia . . . a special case of a more general cognitive phenomenon, namely the disposition to resist the intrusion of anomalous data of any kind into a conceptual scheme whose internal rational coherence is necessary for preserving a unified and rationally integrated self.”20 It is in this context that Angela Davis observes, also in an explicitly Kantian vein, that “in art, knowledges that have always eluded conceptual thought can be rendered possible.”21

Classically, spontaneity is defined as “an action of the mind or will that is not determined by a prior external stimulus.”22 In the first Critique, Kant refers to the human faculty of understanding as “spontaneous” in order to account for the structural creativity of a mind that always exceeds its material. Cognitive spontaneity for Kant names the active power of the human understanding to shape, organize, synthesize and take a stand on what we perceive.23 Thought, Kant argues, is “an act of spontaneity”; it is not a passive registering of sensory data, but a way of taking the data to be something. In one iteration, Kant describes the spontaneity of the understanding in terms of our capacity to combine disparate representations: “We cannot represent to ourselves anything as combined in the object which we have not ourselves previously combined” (KrV B130; my emphasis). One of the chief responsibilities that Kant assigns to the human understanding is the activity of spontaneous synthesis. Kant writes: “The combination (conjunctio) of a manifold in general can never come to us through the senses . . . for it is an act of the spontaneity of . . . the understanding . . . . To this act the general title ‘synthesis’ may be assigned” (KrV B130). All of this means that the proper “object” of one’s thought cannot be specified independently of the spontaneous resources of the knower.24 A major epistemic implication of cognitive spontaneity, then, is that what I take something to be is in excess of that something, and simultaneously allows me to know it. Rejecting the empiricist notion of experience as antecedent raw material for judgment, the Kantian picture points to sense perception as already deeply saturated with spontaneous understanding.25 What appears as given in experience turns out to be always discursively mediated. Analytic as well as critical theory approaches to Kant converge on this key point of the distance from the given, even while differing on its social implications.26

There is a dimension of agency to cognitive spontaneity, insofar as we aren’t wholly determined by the sensory materials that we cognize, although we are still answerable to those materials.27 In “Art and Answerability,” Mikhail Bakhtin writes, echoing an old Kantian problem but pushing beyond the doctrinal separation of art and life: “What guarantees the inner connection of the constituent elements of a person? Only the unity of answerability. I have to answer with my own life for what I have experienced and understood in art.”28 But there is a second dimension to spontaneity, bound up with the first, that I’ll call the “reflexive” dimension, following Henry Allison. The idea is that people have an awareness of actively participating in their own cognition.29 For Kant, the spontaneous synthesizing required for thought is a “conscious combining,” on which the consolidation of the knowing subject itself also hinges.30 The agency dimension and the reflexive dimension of spontaneity are mutually implicated in the spontaneous acts of taking the world to be such and such.31 In an astonishing passage that appears to reduce the self to what Hannah Ginsborg calls a “disembodied locus of spontaneity,” Kant writes: “I exist as an intelligence which is conscious solely of its powers of combination” (KrV B159).32 The consciousness of self turns out to be nothing more and nothing less than a consciousness of spontaneity—a consciousness of the agency of putting relevant things together.33

Spontaneity both provides the condition for knowledge as we know it and holds open the possibility—whether realized or not—for a new epistemic “something else” (to quote Cannonball Adderley) beyond the type of informational “content” that is merely self-replicating and passively beholden to the data—or the ideologies—with which it is imprinted. But as Black musical aesthetics have made all too plain, the new in art is sometimes what is necessary just to make the real perceptible. In his critical poetics of Black music, expressed in fiction and essays, James Baldwin suggests that to play what one hasn’t heard before—that is, to break with prior forms of reference—is precisely to be answerable to what is happening. To play the form one must transcend the form. Paradoxically, the new very often is needed in order to see what’s there, especially when what’s there has been actively hidden from view by structures of oppression and domination or deemed unworthy of representation: “This is what happened, this is where it is,” Baldwin reiterates in “The Uses of the Blues.”34 Conversely, as Baldwin’s narrator sardonically points out in Another Country, the demand to play “what everyone had heard before” (as many jazz bands are pressured to do) dampens the resistance to the violence of the day:

This scene is “sensed” but not “seen” by the down-and-out drummer Rufus Scott, who remains outside the closed door of the jazz club, merely imagining what is taking place inside.36 Thus, Baldwin provocatively uses Rufus’ point of view to enact a “negative mimesis,” gesturing at the spontaneity that isn’t there—having been shut down and foreclosed by a culture that refuses to “hear” jazz as anything other than entertainment.

Spontaneity’s epistemic dimension—its centrality for knowledge production—may have been submerged or trivialized in the dominant reception of Western philosophy and the politics that saturate it. But what is even less frequently acknowledged is the centrality of the epistemic to the history of jazz, and the centrality of the history of jazz to epistemology.37 To take one example I have discussed at length elsewhere, T.W. Adorno’s profound theoretical commitment to genuine cognitive spontaneity underlies his lament about music’s commodification, but also betrays an unwillingness to recognize rhythm in Black music as a formal innovation and an agent of change—that is, as spontaneous in the genuine sense.38 Jazz and popular music, he writes, “divest the listener of his spontaneity”; instead of the music bringing out the critical agency of the listener, the music does it all for you: “The composition hears for the listener.”39 While this analysis may fly when it comes to the club that Rufus Scott did not enter, such pronouncements barely “kiss the hem of the dress of the lady called Jazz,” to quote Chaka Khan.40 The task of interrogating and reanimating extant accounts of spontaneity from the standpoint of Afro-modernist intellectual and artistic tradition remains at the vanguard of securing the future viability of a philosophy of mind that is more than what Aimé Césaire called “pseudo-humanism.”41

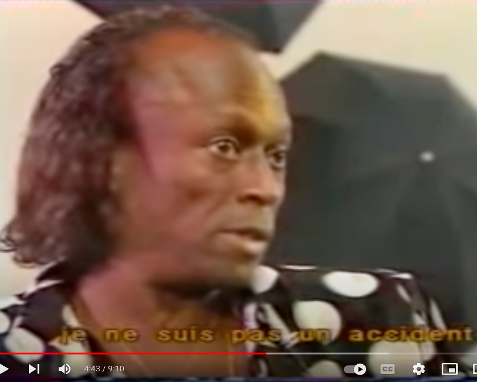

The New Elvin Jones Trio, Puttin’ it Together. Blue Note—BST 84282, 1968

Describing his entire project as “my pursuit of knowledge through the drums,” master drummer Elvin Jones (1927–2004) reclaims the crucial role that synthesis plays in spontaneous knowledge–making, what he invokes playfully through the idiom of “puttin’ it together.”42 The cover art to his 1968 album Puttin’ it Together depicts each of the three trio members (Elvin Jones, drums, Joe Farrell, sax/flute/piccolo, and Jimmy Garrison, bass) as pieces of a puzzle: they are of course both the pieces of the puzzle and the ones “putting it together” in an improvisational exchange, suggesting one way in which jazz—and specifically the rhythm section—completes the picture of the real. This collective “conscious combination” refutes and revises Kant by going beyond the individualist “I think” with which apperception is traditionally associated.43 Drawing on Paul Berliner, Ingrid Monson, Vijay Ayer, and Keith Sawyer, Fumi Okiji opens up critical discourse to the intergenerational, retrospective collaboration that animates jazz practice, broadening the notion of “collective improvisation” beyond the static frame that sometimes restricts it: “past efforts have not been covered over or surpassed by new ones, but are retained and are in fact reanimated (re-worked) by the more recent.”44 This perspective resonates with Chana Kronfeld’s work on the simultaneous, bilateral activation of disparate domains in intertextuality and metaphor, where the agency of all participants, past and present, becomes animated.45 Margo Natalie Crawford writes that the

The possibility, so important for jazz, of reciprocal, intergenerational spontaneity both implied by and erased from Kant’s account is especially salient in a society riddled by what Baldwin called the distinctly American “inability (like a frozen place somewhere) . . . to perceive the reality of others.”47 Indeed, standard accounts of the Bebop revolution and its afterlife in jazz and Black music that manufacture a distinction between “art” and “popular music” may seriously distort what Mark Anthony Neal, drawing on Ray Allen and Farah Jasmine Griffin, theorizes as “black social improvisation”—the crucial “link” between “black musical improvisation and the building and maintenance of black community.”48 Neal writes: “Black popular music . . . frames musical improvisation as an important social phenomenon drawing upon various forms of sociality geared toward building and maintaining community.”49 He continues: “Bebop as a practice and a cultural artifact helped re-create the vitality of the covert social spaces of both the rural south and the urban cities, allowing for the creation of havens or ‘safe spaces’ where ‘community’ could be reconstituted.”50

In his role as bandleader, Jones had each member of the trio contribute a composition to the album. “This is a most unusual trio,” writes the great pianist Dr. Billy Taylor in the liner notes to Puttin’ it Together. Jones would later point to this piano-less trio record, which he led, as one of his favorites.51 Taylor goes on: Within the lineage of jazz drummers, “it was Elvin who developed the concept of using the drums to make a continuous rhythmic comment on what was being played.”52 In an interview with me, drummer and bandleader Dr. Jaz Sawyer explains that by the time of Puttin’ it Together (1968), Jones “had already mastered the quartet format with [Coltrane].”53 Admired for the astonishing power and intensity of his playing, Jones had developed an innovative rhythmic poetics of all four limbs.54 Sawyer reminds us that traditionally, “the hi-hat and the cymbal are considered timekeepers,” but Jones gave these components of the drumkit the freedom of expression and responsivity usually associated with the bass and snare drums. Now the left foot (hi-hat) and the cymbal are also free to become “equal partners” (as Jones once put it) in improvisation’s spontaneity.55 In a 1982 interview for Modern Drummer, Jones explains that the oneness of the kit—the unity of the instrument across all of its components—is the “premise” from which “all the basic philosophies” of drumming should proceed.56 In Puttin’ it Together, Jones moves from consciously [re]combining the components of the kit to now generating new forms of synthesis at the level of the ensemble, paring it down from the powerful quartet to the restrained trio of bass, drums, and sax (or piccolo on the celebrated “Keiko’s Birthday March” and flute on “For Heaven’s Sake”). The fullness of the experimental framework he had worked out in the Coltrane quartet and in larger ensembles afterwards, now resonates in the silences of Jones’ minimalist trio as a bandleader. Here he draws on his long-running partnership with bassist Jimmy Garrison to restructure the rhythm section’s division of labor. Sawyer observes that “on this album it is as if Jimmy [Garrison] becomes the drummer, and Elvin is playing the role of a bass or piano.” Other times, Jones is “playing the chords [on the drums] like a guitarist or pianist would, but without actually playing the notes.” With Coltrane, Jones had worked on “breaking it down”; now he was Puttin’ It Together. In a 1968 interview, just a few weeks after recording Puttin’ It Together, Jones explains:

Jones frequently invoked a painterly vocabulary in his teaching and drum clinics: “There are endless possibilities for changing the color and tone of music through the cymbal tone range,” he explains in a 1973 interview with Down Beat.58 When responding in a 1998 interview to Terry Gross’ question about “moving away from the time signatures and getting freer” in Coltrane’s quartet, Jones deftly navigates the politics of the legibility of Black arts: “There’s nothing strange about abstracts . . . It’s just a musical abstract [here he uses examples from cubism, fauvism, and abstract expressionism]. But the portrait is there, nevertheless.”

In Black Post-Blackness, Margo Natalie Crawford asks, “How has the strategic abstraction of the 1960s and 1970s Black Arts Movement been misread as strategic essentialism?59 Indeed, Jones suggests that Black polyrhythmic aesthetics undo the essentializing binary between representation and abstraction. The master drummer is always both playing the form and transcending the form. Jones’ famous drum solo on “Monk’s Dream” with the Larry Young organ quartet is often misconstrued as being out of time because of Jones’ complex phrasing and multi-faceted engagement with the underlying structure. In actuality, Jones’ improvisation is in a deep dialogue with the melody: “the portrait is there, nevertheless.”60 Black musical innovation all-too-often goes unacknowledged because the listener lacks the background to grasp its complexity.61

But solos are in no way the most important locus of spontaneity in jazz. As saxophonist-composer Darius Jones emphasized to me recently, improvisation is happening all the time in the rhythm section whether in church or on the bandstand—a salient quality of Black sound.62 Rather than seeing jazz as requiring Europeanist authentication, Elvin Jones’ penchant for “abstract conception” (in the words of drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts)63 underscores the Africanist abstraction that pervades modernism itself.64 Drummer Jack DeJohnette observes that “Jones had a way of getting the sound of a whole chorus of Ashanti African drummers in his solos.”65 Dr. Jaz Sawyer emphasizes that for Jones, polyrhythm was so much more than the literal, narrow definitions too often assigned to it by jazz critics. His playing was certainly “in the ceremonial, celebratory spirit of the African Ashanti drummers”; and it was polyrhythmic in the sense of developing far-reaching extensions and elaborations of “the traditional Bembé African rhythm which, as we know, is called 6/8.”66 But studying Jones also requires working against the reification of polyrhythm—against the limited popular understanding of the very concept with which he was most commonly associated. It is presupposed among musicians that 6/8 time is not something peripheral to swing, but rather lays bare the polyrhythmic underpinnings of the swing.67 Elsewhere I have offered a critique of Eurocentric accounts of syncopation in jazz and R&B.68 Polyrhythm is also “what makes a transnational approach to jazz inevitable,” as artist and anthropologist Jadele McPherson’s work makes clear.69 Constantly asked about polyrhythm by journalists, Jones describes it in an interview at Newport Jazz Festival in 1990 as a “Catch-22 term.” Elsewhere he explains polyrhythm as “coordinated rhythms”: “All rhythms do exist individually. However, it is the putting together and the end result of the combinations which is finally judged.”70 Building on his rich rhythm section history with bassist Garrison from the Coltrane years, Jones’ polyrhythmic foundation on Puttin’ it Together becomes so presupposed that he can now free himself up to experiment. On “Sweet Little Maia,” a composition contributed by Garrison in honor of his daughter, Jones brings the melody back in from Garrison’s double-stop bass solo at 6:39 with an eight-bar playful minimalism of swinging abstraction on the brushes, employing what Sawyer calls a “tap dance approach.”71

In her homage to Jones, drummer-producer Terri Lyne Carrington, director of the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice notes that “people always talk about the forceful part, the power. That’s not the first thing I hear.”72 Indeed, both Carrington and her mentor Jack DeJohnette have honed in on the muted expressivity of Jones’ brushwork during the Puttin’ It Together period.73 Analyzing Jones’ drum solos in a live precursor to the 1968 trio (the recently-released Live at Pookie’s Pub, recorded in 1967), Carrington remarks: “Even when the time breathes . . . you can hear when he goes to the bridge.” Saxophonist-composer Ravi Coltrane concurs: “No matter where he was within his musical phrase, he always outlined those forms. You could hear him coming around the corner, even if it was stretched out . . .”

3. What Spontaneity Isn’t

“[Jazz]’s most extraordinary achievement . . . is ‘the

“Elvin Jones called his album “Puttin’ It Together,” not ‘Throwin’ it Together,’” quips Dr. Jaz Sawyer. With Kant and Jones, I have been pursuing an account of spontaneity which re-claims it as a feature of the understanding, of knowledge production characteristically expressed in the form of “conscious combination” rather than a caprice of the passions. But the work of divesting spontaneity of its primitivist and racist baggage remains unfinished.75 There is a developmental trajectory implied by Kant’s and ensuing Romantic accounts of spontaneity that should not be ignored. The philosophical reception of spontaneity has often postulated the idea of a pre-spontaneous way of life considered more “primitive”—the developmental stage notoriously associated with “babes and beasts.”76 Cognition is forced into hierarchical form, becomes racialized, and is enlisted as an agent of racialization.77 By the same token—and this is a much less explored perspective—the almost tacit consensus that equates spontaneity with voluntarist, liberal notions of “free choice” seriously distorts the account of spontaneous conceptualization I have been elaborating here. Daniel Warren has suggested to me that, contrary to the voluntarist traditions that have persistently been read back onto Kant, Kant’s notion of cognitive spontaneity has little to do with the freedom of picking one representation over another, and hence does not conform with the liberal notion of “choice.” In the context of jazz improvisation, Scott Saul points out that postwar jazz musicians contested the “intellectual axiom of 1950s America” . . . that “‘freedom’ was umbilically joined to the ‘free market.’”78 Similarly, Adorno feels compelled to clarify this culturally illegible nuance in 1959: “On the one hand . . . ‘Spontaneität’ means the capacity for action, production, generation. On the other hand, however, it means that this capacity is involuntary, not identical to the conscious will of the individual.”79

What I would like to foreground is that rhythmic and verbal art can move us beyond developmental epistemologies to combat the appropriation of cognitive spontaneity and its dissolution into cliché. In different formations, these clichés have attended the reception and perception of jazz improvisation as well as of literature, skewing, for example, the Romantic spontaneous poetic expression of emotion, and modernist renditions of the vagaries of consciousness.

If some of the nuances of Kant’s notion of the mind’s spontaneity have often fallen out of view in its afterlife, the same can be said of the reductive construal of Romantic notions of spontaneity tout court, as is most clearly shown in the reception of William Wordsworth’s theory of poetry. Claudia Brodsky has emphasized that what has come down to us as Wordsworth’s famous formulation that “all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” is a distorted half-quotation. The full statement is, “For all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: and though this be true, Poems to which any value can be attached were never produced on any variety of subjects but by a man who, being possessed of more than usual organic sensibility, had also thought long and deeply.”80 As Brodsky notes, “the truncated version of Wordsworth’s definition has long been the single lens through which his own work is most readily, while disparately viewed.”81

The result is the limited visibility of the alternative, more nuanced accounts of cognition that are encoded within these artistic practices and trends (from Wordsworth to Jones to Morrison). The primitivist and implicitly racist discourse on spontaneity that is so common in Western culture—associating it with the irrational, formless flow of “anything goes”—does violence to subjectivity as such by excluding from it all structure and epistemic value. Conversely, valorizing spontaneity in art and expression has been used to pit it against theoretical reflection, giving thought itself a bad name by equating it with rigid pre-determination. This is why I made above the rather bold suggestion that the reductive treatment of Wordsworthian spontaneity and the racist denigration of spontaneity in jazz belong to the same ideological paradigm. Fumi Okiji has confronted this conceptual double bind more boldly than any. She writes: “Jazz, interpreted as a manifestation of freedom from intellectualized approaches to creative expression, is understood by the primitivists to come from a people with direct access to a primal human essence all but lost by their European counterparts.”82 Sometimes this has come in the form of the racism of praise. To give one example endorsed by Alain Locke, the Belgian jazz historian Robert Goffin waxes poetic in the 1930s that “the technique of jazz production has been rationalized by Ellington . . . he has gradually placed intuitive music under control.”83 At the same time, as Robin D.G. Kelley has shown, this primitivist embrace was the price for “plac[ing]” black musicians squarely within the pantheon of surrealism’s founders.”84 “‘What Breton and [Louis] Aragon did for poetry in 1920,’ noted Goffin, ‘Chirico and Ernst for painting in 1930, had been instinctively accomplished as early as 1910 by humble Negro musicians, unaided by the control of that critical intelligence that was to prove such an asset to the later initiators.’”85 Those very primitivist perspectives, of course, were often reappropriated by jazz artists fashioning an acerbic musical critique. Think of Duke Ellington’s Money Jungle trio album from his later years, or, in the literary domain, of Morrison’s defamiliarized flipping of the concept of “jungle,” focalized through Stamp Paid’s point of view in Beloved.86

Jack Kerouac, “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose” (1957); Miles Davis, Miles: Noir sur blanc, dir. Jacques Goldstein (1986)When beat generation writers referred to their work as “spontaneous,” they in many cases reiterated the same binary oppositions that Okiji calls attention to.87 In “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose” (1957), Jack Kerouac claims to model his prose poetics on jazz, by championing what he calls “blowing (as per jazz musician) on subject . . . swimming in sea of English with no discipline other than rhythms of rhetorical exhalation and expostulated statement.”88 The complex rhythmic structure of Kerouac’s own prose, however, belies the reductive understanding of spontaneity that his essay asserts.89 In fact, Kerouac shared the bill with Elvin Jones at the Village Vanguard in the very same year that “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose” appeared, an encounter that did not prove as amicable as Jones’ collaboration with Allen Ginsberg.90 His love for jazz notwithstanding, Kerouac’s view of spontaneous writing, or “blowing” as indiscriminate, limitless, and undisciplined does not comport with that of Miles Davis, who tirelessly insisted in public interviews—as in the French documentary pictured here—“I’m no accident.”91 Davis reminds viewers of the grueling (and still somehow culturally invisible) process of practicing one’s horn—the deliberative work that is the obvious precondition for improvising, what Walton Mayumba deftly terms the “tutored spontaneity of jazz improvisation”92: Je ne suis pas un accident. Davis adds: “White people give the Black musician in America the attitude that ‘you don’t have to practice, you got it, it’s natural.’”93 I have been suggesting that many of the racialized inflections that have accrued around the term “spontaneity” in the West can be brought to the fore by focusing on jazz improvisation – with “improvisation” as a cognate term for spontaneity.94 The philosophy taught by jazz musicians through and about their art includes the insight that their music performs conceptual work – but in a way that continually contests the “divisions between life and thought” that have plagued the Western philosophical tradition.95 Indeed, the possibility of ascribing spontaneity to conceptual thought still remains totally counterintuitive within the dominant intellectual culture; and yet that is precisely what both Kantian spontaneity and jazz improvisation maintain. For me this is not just a matter of theory, but part of the lived experience I have shared, as a pianist, with my musical collaborators.96 Questions about improvisation put to musicians after shows by certain well-meaning listeners can be painful because it would take so much work to undo the presuppositions that inhere in the question, “Were you improvising when you did that?” To say “yes” would be to capitulate to the primitivist assumption that jazz is a type of unstructured magic; to say “no” would be to give in to the contrary assumption that it’s all planned out in advance. According to this logical bind, the music is legible as creation only on the assumption that it is pre-meditated—a sinister view from which it follows that structured forms are by definition doomed to miss the moment. It is as if something in the colonial tongues, and their attendant intellectual cultures through which many Americans speak makes it difficult to specify an intermediary position between a scripted score and the subjective play of “anything goes,” between fixed structure and arbitrary flow. In contrast to these discourses, jazz musicians show that one can play, speak, or think in a structured manner in the moment. But this philosophical possibility is exactly what is foreclosed by the manufactured dichotomies I have sketched out here. Historically, codified musicology and journalistic jazz criticism in the West have all too often had a thinly-disguised colonizing function when it comes to discussions of Black music. Matthew D. Morrison elucidates the racialized gulf between what he calls “ephemeral Blacksound” and the sheet music industry, a context where songs are “heard and legally taken up by white writers and publishers who had both the means and the structural access to claim ownership over . . . performed material.”97 This publication history of early blues and ragtime, going back to the nineteenth century, describes how white markets—and epistemologies—have mediated the conditions under which blues and ragtime become legible as artistic products and texts. These dynamics, illuminated by Morrison, are a necessary backdrop for understanding the ensuing problematic history of jazz criticism up into the twentieth and twenty-first century. Jazz practitioners themselves, of course, and the people close to them, have continually pushed back against the discursive formations imposed upon the music from without, calling into question especially the racist presuppositions that sometimes attend “improvisation” in its dominant reductive use. James Baldwin’s intimacy with the music is evident in his witty rejection of the very locution “improvisation” in a 1979 essay, written as a critique of jazz criticism of the time: “Go back to Miles, Max, Dizzy, Yardbird, Billie, Coltrane: who were not, as the striking—not to say quaint—European phrase would have it, ‘improvising’: who can afford to improvise, at those prices?”98 As Editor Randall Kenan writes: “Though Baldwin originally wrote this piece [“Of the Sorrow Songs: The Cross of Redemption”] as a review of James Lincoln Collier’s The Making of Jazz (1979), the essay turns into a meditation and manifesto about race and music.” Going back to Zora Neale Hurston, significant Black music criticism has been written in the genre of the book review, correcting the record.99 George E. Lewis writes that “buried within th[e] Eurological definition of improvisation is a notion of spontaneity that excludes history or memory.”100 This goes for both the ignorant erasure of jazz’s intertextual idiom and quotation, and for the historiographical erasures that such a limited view of improvisation enables.101 To redress these distortions, saxophonist Gary Bartz, following master composer and bassist Charles Mingus, has in recent years revived the notion of spontaneous composition as a substitute for the tainted term “improvisation.” Bartz’ and Mingus’ usage here philosophically resonates with Elvin Jones’ notion of jazz’s spontaneity as “putting it together”:

Gary Bartz is alluding here, among other sources, to Mingus’ critical reflections in his award-winning liner notes to his 1972 album Let My Children Hear Music.103 In this liner note essay, titled “What is a Jazz Composer?,” Mingus refers to his artistic project as that of a “spontaneous composer,” thereby challenging the ideological straitjackets that constrain aesthetic possibility on both sides of the racialized divide between so-called “classical” and “jazz” music.104 He makes a claim for the historical indispensability of Black artistry for expanding the music’s range—quite literally, extending the upper register of musical instruments like the trumpet. Jazz musicians continually prove “that the instrument can do more than is possible . . . the range has doubled in octaves.” For Mingus and his ten-piece ensemble on Let My Children Hear Music, the expansion of register and instrumentation into new domains becomes both a metaphor for and a literalization of stretching beyond the racist strictures that have constrained the orchestra institutionally and philosophically. His notion of spontaneous composition is the philosophical equivalent of a new harmonic voicing or rhythmic syncopation; that is, something difficult to think under existing concepts and yet instantly made conceivable the moment it is articulated. It is itself an example of new synthesis, spontaneous thought instantiated.105 The essay “What is a Jazz Composer?”, then, is not only a matter of rectifying perceptions of jazz; classical music remains impoverished so long as the “composed” is understood to be incommensurate with the “spontaneous.” “Adagio ma non troppo” on Let My Children Hear Music is an “improvisation on symphonic form” that Mingus specifically refers to as a “spontaneous composition” (12, 55): “I always wanted to play classical music—not Beethoven or Bach or Brahms but improvise and compose new string quartets” (55). When I asked composer-guitarist John Schott to comment on Mingus’ notion of spontaneous composition, he emphasized Mingus’ long-standing relationship with drummer Dannie Richmond, who played on Let My Children Hear Music among at least three dozen other recordings with Mingus over the course of twenty years: “They worked out musical concepts together,” he notes, emphasizing the reciprocal reflexivity that, as we have seen, is frequently left out of discussions of spontaneity, Kantian or otherwise.106 As Mingus said [quoted in Mingus Speaks], sometimes the mind-reading got so intense, that “it made him start to believe in God.”107 “And You and I know exactly what that is,” Schott says to me. “That is a musical accomplishment that can’t be put on paper; even one instance of it can never indicate the totality of it.”108 Mingus’ theorization of spontaneous composition is in stark contrast to the legacy of jazz criticism all the way at least into the early 1990s. See, for example, Ted Gioia’s award-winning book, The Imperfect Art: Reflections on Jazz and Modern Culture, named a “Jazz Book of the Century” by Jazz Educators Journal. Oddly enough, the following passage which equates spontaneity with formless unreflection appears after Gioia’s groundbreaking chapter debunking “The Myth of Primitivism”: “The very nature of jazz demands spontaneity . . . . The virtues we search for in other art forms—premeditated design, balance between form and content, and overall symmetry—are largely absent in jazz . . . [The jazz musician’s ] is an art markedly unsuited for the patient and reflective.”109 I have tried to show in this section that by pushing back against what spontaneity isn’t, Black music has continually defended philosophical possibilities that have been otherwise denied and foreclosed. 4. Toni Morrison’s Drums, the East St. Louis Massacre, and the Silent Protest Parade come aboard East Saint Jazz’s cyclic jam session, In an interview about her 1992 novel Jazz, Toni Morrison states: “Jazz was my attempt to reclaim the era from F. Scott Fitzgerald, but it also uses the techniques of jazz—improvisation, listening—to ask questions that I want to ask myself.”111 For Morrison, that spontaneous dimension by which the mind actively and interactively constructs its knowledge is indispensable. Her work suggests that verbal art can follow jazz in holding non-deterministic, spontaneous ways of knowing that are negated under the reigning social order.112 Herman Beavers observes: “Jazz is Morrison playing the changes on Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.”113 Indeed, Morrison’s focus is akin to what Saidiya Hartman would later theorize as “the revolution before Gatsby.”114 Morrison’s fiction redresses the co-optation of the jazz age, but she brackets that historiographic corrective as even less important than the capacity “to ask questions that I want to ask myself.”115 Jazz, for Morrison, thus emerges as a knowledge project. Her narrative process in Jazz generates specific questions but also seems to engage the question form itself as the site of spontaneous inquiry. She writes:

Morrison’s image of the book that “watches itself think and imagine” re-animates the deep links between self-awareness (what Kant called “apperception”), knowledge and spontaneity. Her attention to the formal techniques (the “artifice”) undergirding the appearance of spontaneity resonate with Morrison’s 2004 critical analysis of the jazz-informed paintings of Romare Bearden117: “Choice of color, form, in the structural and structured placement of images, in fragments built up from flat surfaces, rhythm implicit in repetition and in the medium itself – each move determining subsequent ones, enabling the look and fact of spontaneity, improvisation.”118 Not much jazz music is played in the novel Jazz; indeed, we seem to find jazz just where it is nowhere to be found.119 Instead, Morrison makes it possible to strip back the clichés that have impeded the registering of subversive sound in the American historical imagination. Her refusal to present, even represent jazz to us as a finished product or content of narration evokes the long history of Black musical artists who themselves contested the very term “jazz” as a (white) misnomer for the music that they innovated, as we have seen.120 Stephen Best has shown how Morrison’s novel A Mercy radically defamiliarizes the concept of race by returning to a moment in time when the concept was not yet fully consolidated.121 The novel Jazz may perform a similar function by beginning at a moment when the concept of jazz had not yet been fully appropriated for white commercial markets.122 As Daphne Brooks puts it, Morrison’s Jazz is “confounding to some because of its refusal to literalize the jazz experience in America.”123 The only sustained dramatic situation in which live music occurs in the novel is in the “Fifth Avenue March” scene, a fictional re-writing of the 1917 Negro Silent Protest Parade in New York City. This highly structured political action, described by James Weldon Johnson in his book Black Manhattan as “one of the strangest and most impressive sights New York has witnessed” was organized by the NAACP in response to an explosion of extreme violence by a mob of white men and women against Black communities in East St. Louis on July 2 and 3, 1917, but preceded by months of terror.124 The Fifth Avenue March scene is a pivotal moment in Morrison’s novel where we see one of the central characters, Dorcas, as a child-survivor of the massacre now witnessing the protest parade. The massacre, considered one of the worst in American history, was documented by NAACP co-founder and pioneering anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett who courageously traveled to East St. Louis on the following day to collect local testimony.125 In recent years, historian and Alderman Terry Kennedy, whose father survived the massacre, has explained in an interview for professor Denise Ward-Brown’s documentary film Never Been a Time (2017): “Hundreds of White Americans attacked the Black section of East St. Louis and tried to burn it to the ground, killing three hundred people but dislodging thousands from the city.”126 Ward-Brown’s film, premiering on the centennial of the massacre, “questions and analyzes the coded language” and series of erasures with which the massacre entered (or did not enter) the official historical record. For a century, it has been referred to by historians as the “1917 race riot,” following the terminology which was used by Congress in 1917127; as Dr. Andrea Boyle points out in the film, the term “riot” continues to obscure anti-black violence by white Americans today. Historian Charles L. Lumpkins, author of American Pogrom: The East St. Louis Riots and Black Politics concludes that the violence needs to be understood as “part of an ethnic cleansing campaign.”128 He elects to use the term “pogrom” for this study because the violence has a “political importance”—it cannot be explained simply by “white workers’ fear of black competition,” as the history is usually told, but needs to be understood also as a systemic attack on “African American community building and political involvement.”129 Judge Milton. A Wharton explains this reframing: “A pogrom is something that has a desired direction. In the East St Louis Pogrom, the interests of the people who perpetrated this incident was not just to kill Blacks or to burn homes. They wanted to remove the African-American presence from East St Louis.”130 The term “pogrom” is also adopted by Members of The East St. Louis 1917 Centennial Commission and Cultural Initiative (CCCI), including many Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (SIUE) alumni and faculty, who organized a series of “cooperative events” in 2017, including the Sacred Sites and the Historical Marker projects.131 CCCI commissioners include editors of the literary journal Drumvoices Revue Darlene Swanson Roy and East St Louis poet laureate Eugene B. Redmond, a close collaborator of Toni Morrison. “There has never been a time” when the 1917 massacre “was not alive in the oral tradition,” asserts Eugene B. Redmond,132 whose poem in honor of Miles Davis is my epigraph for this section.133 Davis, who was born in 1926 and raised in East St. Louis, tells Quincy Troupe in his 1989 autobiography: “It was there, back in 1917, that those crazy, sick white people killed all those black people in a race riot . . . . That same year black men were fighting in World War I to help the United States save the world for democracy. And it’s still like that today. Now, ain’t that a bitch. . . . When I was coming up in East St. Louis, black people I knew never forgot [the massacre].”134 In “Just Before Miles: Jazz in St. Louis,” William Howland Kenney points out that “grass-roots musical training for boys in black St. Louis emphasized the cornet and trumpet,” giving birth to the “black St. Louis school of jazz trumpeters from Robert Shoffner to Clark Terry” to Davis.135 The East St. Louis jazz milieu, an intellectual, artistic and activist center that also nurtured the epoch-making “doyenne of dance” Katherine Dunham, embodies what Morrison describes as the “intergenre sources of African American Art . . . . the resounding aesthetic dialogue among artists.”136 Interestingly, Morrison’s character, Dorcas resonates strongly with Josephine Baker, who survived the East St. Louis massacre as an eleven-year-old.137 Tyfahra D. Singleton notes that Josephine Baker at various junctures “chose to begin the story of her life with the East St. Louis massacre of 1917—a collective trauma in place of her personal ones which came years before.”138 In Henry Louis Gates’ 1985 interview with Baker and James Baldwin, Baker remembers: “All the sky was red with people’s houses burning.”139 In her speech at the 1963 March on Washington, Baker returns to the fire as a violent catalyst for a life in jazz and activism, as well as for her exile:

July 28, 1917. The NAACP Silent Protest Parade on Fifth Avenue. Photograph by Underwood and Underwood. James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library141There are four drummers in this image of the 1917 Silent Protest Parade. The two drummers in the middle are playing snare drums, with the drummers on either side playing field drums which are made of a thicker canvas, but still possess snares. As drummer Savannah Harris pointed out to me, the absence of a bass drum (which would have been central for a military parade) suggests that these drummers were playing in a somber style.142 Yet given that this is a silent protest, a crucial question taken up by Morrison’s fictional rewriting of the march becomes: How did the sound of the drums help to constitute this silence? One single phrase repeats with disarming uniformity across historical accounts of the landmark parade: “muffled drums.”143 The “muffled drums” reflected a definite sonic intention on the part of the planners. The NAACP memorandum distributed in advance of the march read: “The laborer, the professional… —all classes of the Race—will march on foot to the beating of muffled drums.”144 The march’s organizers included Madame C.J. Walker, W.E.B Du Bois, and James Weldon Johnson, who was the march’s sonic architect, credited with making the decision to employ the strategy of a silent march.145 He can be seen in the image marching next to Du Bois. Thus, cooperative engagement —not detachment—marks Johnson’s work as a historian of the march, which he covers in his Black Manhattan. For someone with as highly-trained a poet’s ear as Johnson, his choice of a silent march is profound. The phrase “muffled drums” appears in poet, anti-lynching crusader, and march organizer Carrie Williams Clifford’s poem “Silent Protest Parade,” from her collection The Widening Light (1922):

Clifford uses modernist monorhyme (the nasalized “m/n” ending) to make prosodically and rhythmically present the sound of the muffled drums. But the unified and unifying sound of this rhythmic restraint (“ten thousand of us, if there was one”) contrasts sharply with the musical expectations of white spectators looking to be entertained:

Clifford’s work illustrates the way that poets join and anticipate the refusals of jazz musicians to capitulate to primitivist projections that negate the music’s spontaneity by reducing it to its entertainment value. Morrison’s novel Jazz is saturated with these historical echoes. The 1917 Silent Protest Parade is described in the novel through the eyes of Alice, a churchgoing, morally conservative woman of the older generation in charge of her recently-orphaned niece Dorcas, whose parents were murdered during the massacres in East St. Louis just weeks before the March. Alice struggles to make sense of the sounds she hears, and to sort out the jarring juxtaposition between the “lowdown,” “below the sash” music she disapproves of and the differently-valenced drums that accompany the protest on Fifth Avenue.148 The way Morrison, through Alice, puts together the jazz-blues of the juke joint with the muffled drums of the protest cracks open the clichés that accumulate around the concept of jazz and exposes the colonial regime that artificially splinters Black music into distinct genres.149 Morrison is evoking narratologically what saxophonist and cultural historian Howard Wiley calls the “oneness of the music.”150 Through competing modes of understanding expressed as shifts in point of view, Morrison’s novel disqualifies ideas of authenticity that are persistently projected onto Black American musics and their representations. She uses the moment when Alice takes note of the drums to stage an encounter between apparently incommensurable modes of knowing:

The drums evince spontaneity in the true, epistemic sense that I have been pursuing in this essay. Their interpretive power, what I have called “the ability to produce new knowledge, in contradistinction to self-replicating discourses” emerges in Morrison’s passage as a direct response to the exhaustion of available language, and specifically to the failure of affirmations like “all men are created equal” to refer.152 The agentless syntax in the phrases “what was possible to say/what was meant” itself formally articulates the historical erasure in question, but also paradoxically turns the drums (the indirect object of the sentence) into the conveyer of an intentionality that reaches even beyond the collective, towards some impersonal universal. The drums, with their deep imbrication with Black critical epistemologies serve in Morrison’s text as the paradigm for a cognitive act of synthesis that is gestured toward but never fully realized in a society where the possibility of “putting it together” has been violently foreclosed.153 Even Morrison, under whose pen language could not have been more vibrant, makes it clear that the music steps in where the language of official history fails, the rhythm of the drums taking on the burden of the linguistic. Language, in becoming more like music, becomes itself again.154 The putting-together of drums and verbal art has been the crux of the decades-long collaborative projects spearheaded by the aforementioned East St Louis Poet Laureate Eugene B. Redmond, the author of the critical history Drumvoices: The Mission of Afro-American Poetry (1976), as well as founding editor of Drumvoices Review: A Confluence of Literary Cultural and Vision Arts (opening issue 1991/1992). Throughout the 1970s, Morrison and Redmond worked together intensely on the posthumous publication of the poetry and fiction of Henry Dumas, who also lived and taught in East. St. Louis and SIUE.155 Just as salient here is Morrison’s work as editor on the groundbreaking volume Giant Talk: An Anthology of Third World Writers, compiled by St. Louis poet (and Miles Davis literary collaborator) Quincy Troupe.156 In recent years, scholarship has increasingly focused on Morrison’s profound impact on African-American literary publication in her capacity as editor for Random House.157 What has been less explored is how Morrison’s collaboration with jazz-affiliated poets—specifically, with East St. Louis poets—might enrich contemporary readings of the novel Jazz and its reimagining of the Silent Protest Parade.158 Redmond traces the portmanteau “Drumvoices” (and its attendant concept, refusing to separate drum from voice) back to his collaboration with dance and anthropology pioneer Katherine Dunham, who, like Dumas, took a teaching position at SIUE.159 Dunham, the “mother of modern dance,” claimed East St. Louis as her activist, intellectual and artistic home.160 This East St. Louis-based theorization of drum and text, drum and voice provides a rich background for Morrison’s novel and for the drums’ reclamation of spontaneous knowledges in particular. As Morrison’s Fifth Avenue march scene continues with little Dorcas and her aunt Alice looking on to the protest parade, the drums express their knowledge by holding space for the “gap” between young Dorcas’ trauma during the East St. Louis massacre (as imagined by Alice) and its available descriptions: